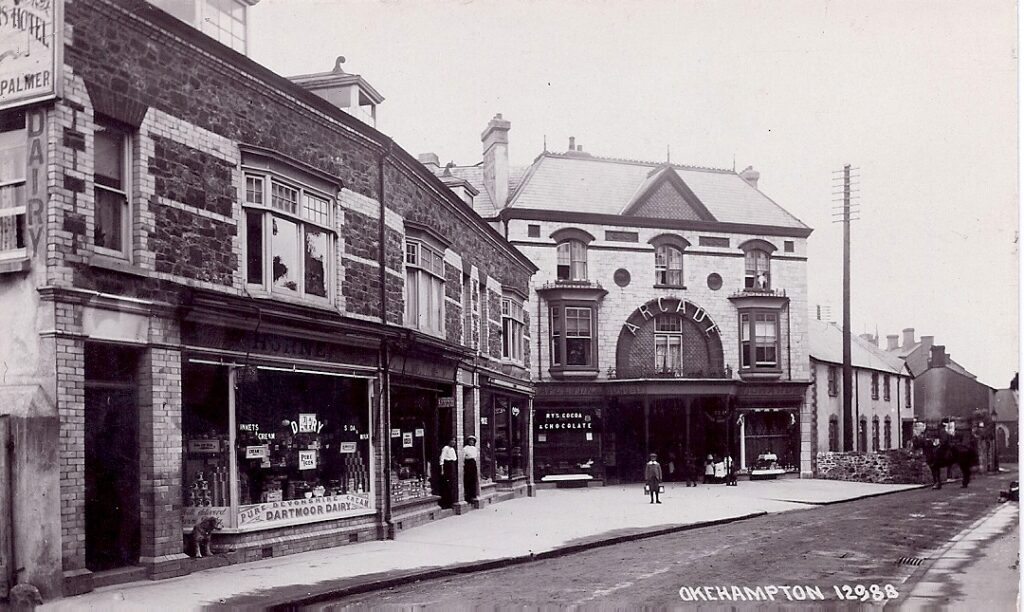

The Okehampton Food Bank started the year facing the most severe financial crisis in half a century. Factors such as the energy crisis, the war in Ukraine, and the significant arrival of refugees through the Afghan Resettlement Scheme put tremendous strain on the food bank’s staff and resources.

During the peak of this crisis, we were assisting 165 people a week. This support was made possible by the community of Okehampton yet; the governing body overseeing the food bank chose to withdraw their support and close us down in July.

Regardless of the problems forced upon us, this year we have provided food to make 9500 meals. This was lower than 2023 when the number was 11230 meals but, we were out of action for the whole of July this year due to circumstances beyond our control.

We have reached our goal thanks to you!

Our mission when we re-launched in August was to remain operational until Christmas! With your help, we have done this. Which is a testament to the support we received from the people of Okehampton.

We’ve managed to overcome the cost-of-living crisis, rising inflation, increasing demand and unnecessary shutdowns and we are still here to assist the less fortunate in Okehampton.

The dedicated volunteers passionately pushed for the food bank to continue its operations rather than transferring its resources to another private business, but sadly, their appeal was refused.

So, with an initial donation of £25, The Okehampton Food Bank moved to our new location at the Ockment Centre and, for the first time in its 16-year journey, became genuinely independent.

We have revised our Mission Statement

The Okehampton Food Bank’s primary mission is to alleviate food insecurity and enhance the well-being of the community’s most vulnerable residents.

To address food insecurity, the food bank provides food and essential household items to local people facing demonstrable challenges such as low income, benefit delays, homelessness, disability, loss of income, rising costs of living, and short-term needs for refugees.

The food bank ensures that the families it serves receive a healthy, nutritionally balanced supply of food, including fresh produce, eggs, and dairy. Beyond food distribution, the organisation offers supplementary services to help address widespread poverty in the community by connecting people to other local support agencies.

By meeting nutritional needs through food aid, the food bank frees up recipients’ limited resources for other essential expenses. Overall, the food bank’s holistic approach aims to not just provide temporary relief but to empower vulnerable community members and address the root causes of food insecurity.

The Harvest Festival produced donations from 14 schools, 16 Churches, 9 local businesses and hundreds of local people.

The day before our Christmas closing a couple arrived in the food bank, with a wonderful Christmas donation of chocolates, cakes, biscuits and other yummy ‘extras.’ This same couple has also brought us Easter eggs every year since the current coordinator took over the food bank in 2021.

Malcolm said,

“I’m ashamed to say it but I don’t even know the couple’s name because they always visit when we are really busy but, they know the work they do privately for the food bank, and this makes all the difference in a sea of pasta, porridge and beans.”

“Much of the food we receive is vital sustenance for hungry families and the donations we ask for don’t change much but, this lovely couple go the extra mile and bring in the extras that make struggling families feel whole once again.

We have attended several conferences this year enabling us to be at the forefront of food poverty resolution in Okehampton.

We have greatly expanded our referral agencies which means we do not have to self-refer families to us but rely solely on Health and Social care professionals to do what they do best. We thank Citizens Advice and Community Links for their unwavering support this year. We also have families, (we don’t have clients) who we refer to our partners to get the extra help they need.

How your donations are making a difference.

A true story…

A mother of three young children faced a challenging financial crisis, finding it hard to provide sufficient food for her family.

For 18 months, she depended on The Okehampton Food Bank’s support to survive.

However, in June of this year, her situation improved significantly when she secured a stable job. With her new income, she was not only able to buy enough groceries for her family but also received a promotion shortly after starting. This advancement enabled her to pay off the debts that had accumulated during her unemployment.

Reflecting on her experience, Grace (a pseudonym) expressed heartfelt gratitude for the essential help the Okehampton Food Bank offered during her struggles.

“I truly don’t know what I would have done without you,” she shared in a recent letter to the food bank coordinator.

“Your assistance was a lifeline that kept my family fed and cared for until I could regain my footing. I am incredibly thankful you were there for us when we had no other options.”

Grace’s journey highlights the critical role community resources like food banks play in supporting families in need, helping them navigate tough times and move toward stability and independence.

The dedication of our volunteers

The unwavering commitment of our volunteers is undoubtedly a key factor in the success of The Okehampton Food Bank over the past 16 years. Their efforts, along with the generosity of our donors and the support from Waitrose, empower us to assist countless individuals in need.

Mary (not her real name,) has dedicated 12 years as a volunteer at Okehampton Food Bank, providing essential support to those in need within our community. Her commitment to helping the less fortunate has made a significant impact over the years.

Through her efforts, Mary has become a vital part of the organisation, ensuring that food and resources reach those who require assistance. Her long-standing service exemplifies the spirit of community support and compassion.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the individuals, churches, schools, local businesses, and charitable organisations in Okehampton who have joined us in the battle against the social injustice of food poverty throughout 2024.

Your support has been invaluable, and it truly makes a difference in the lives of those in need. Together, we are making strides toward a more equitable community, and we appreciate every effort made to help those facing food insecurity.

May Christ’s light shine on you all this Christ-mass.